I was reading Lucy Knisley's newest comic today, and when I got to the middle, I started crying. I called Daniel, but his phone was busy. I wanted to share my happiness with someone who gets it, with someone who reads Lucy's comics with my same enthusiasm (D and I read almost all the same comics, so this is easy for us to do). I've been reading her autobio and travel comics for so long, it feels like I know her personally. I am invested in her life like a friend.

This is the strange thing that webcomics--which are released with a regularity not afforded to printed mediums--and Twitter can lead to: a feeling of friendship with people who don't know you. It's complicated, but I wouldn't trade the intimacy of Twitter (something I try, myself, to employ because I understand how powerful it can be) for the real-acquaintance reality of Facebook ever. Ever.

Sometimes it feels a bit like being in high school, like admiring the Cool Kids from the sidelines*. This sensation could be further complicated by my profession. I write fiction. I really do spend a lot of time being intimate with people who aren't real. And my favorite winding-down hobby is, as a matter of fact, watching TV. I don't love all television, but the shows I do love, I LOVE. I regularly marathon the X-Files and Veronica Mars. And then I have dreams where I'm working with Scully to save Mulder and I'm also chilling with Marlo Meekins and Madéliene Flores and Erika Moen, and then I wake up feeling very, very ungrounded in reality. I am a wallflower in half-real worlds more than I am a participant in the "real"-real one. I wake up and miss hanging out with the friends who don't know me.

Yes, I do wish I was "real" friends with more cartoonists. I am a little envious of their group, of the conversations I see because of the people I follow, and sometimes I feel like a voyeur, undeserving of seeing so clearly into their lives. But it's not like that at all. It's like Lucy says in her comic: "We're not strangers. Life, change, work...it's universal. It connects us." How great is it to feel like you can celebrate the happiness of someone you barely know? I like it, a lot. I like the way it connects me on a very empathetic level with people whose professional work I have admired from afar for years. Sure, on the one hand it feels sadly like fiction, but since the point of fiction is to make us feel empathy towards people who aren't real, that's pretty okay. Why is it bad for me to slip so easily into feeling compassion for strangers? It's not. It's not bad at all. So even though I sometimes find myself missing friends I've never had (which does feel rather like a perverse nostalgia), I am glad we live in a time where this is possible. I'm glad we live in a time where I could possibly provide comfort or a sense of inclusion for someone else.

Though, Jennifer Jordan (one half of Darwin Carmichael) and I are Twitter friends, so...I guess it's not all fiction. :)

*The nicest group of cool kids ever. Receiving an RT or a reply from someone you admire feels like Christmas. It's a good thing to keep in mind, fellow writers. If you ever make it big (or big enough to have even one fan), you can make someone's day--heck, week--with a simple smiley face.

who the heck knows anything, anyway

Monday, August 19, 2013

Tuesday, August 13, 2013

Book Review: The Nao of Brown

Glyn Dillon’s The Nao of Brown (SelfMadeHero, 2012)

The Nao of Brown is so close to being good.

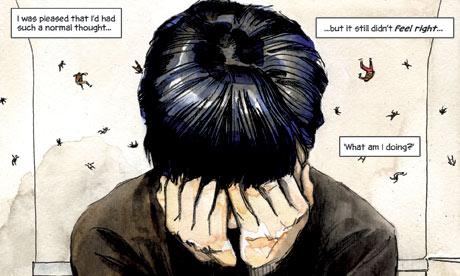

Dillon’s art is phenomenal. It carries the story. The prose is occasionally stilted, very ellipses-heavy in both dialogue and narration, which draws away from the story more than once. However, that art!--absolutely beautiful. And Dillon’s illustrative skills are no one-trick pony; the story takes place in both the real world (narrated by protagonist, Nao Brown) and in the pages of a fictional Manga series--Ichi--by a fictional author by a similar name. A comic within a comic: very meta. Both sections are illustrated in separate, distinct styles. Both are beautiful.

|

| image from The Guardian's review |

The exciting part of Nao is that the protagonist has obsessive-compulsive disorder. As far as most people understand, OCD is an excessive hand-washing and organizational problem. It’s disheartening that, even now, most mental disorders are still commonly viewed as one or two stereotypes that can be dismissed as “quirks”. So this is what made Nao promising. Nao Brown, a young Japanese-English woman, suffers from OCD that manifests in violent intrusive thoughts. Her coping mechanisms are realistic, her self-blame is realistic, it’s all incredibly realistic. Only, sigh, there’s a big problem:

The moral. The big reveal at the end of the story. This is not really a plot spoiler, but it does come at the end of the book, so only continue reading if you want, but it’s too important to not be addressed in a review. Essentially, during the tidy-bow-wrapping of an ending, the takeaway is that Nao discovers that her OCD is her “fault” and that practicing meditation made her realize that she was making a bigger deal out of it than it was.

No. Incorrect. This is terrible. First, people who do not have OCD (and possess the most basic knowledge of it) will think it can be fixed by pure willpower, that it’s not a “real problem.” Second, people with OCD could come to the conclusion that they are bad people for not being able to handle their problem, or that they are bad people because they have intrusive thoughts, etc.

“You’re overreacting,” you say. “One sentence can’t have that kind of effect on a person.”

I have OCD. The truth comes out. That is why I was excited to read this book, and why I was so disappointed by it. Many people do not understand what OCD is or how it affects a person’s life. This is resoundingly evident in the media treatment (Monk, for example, in which all of the supporting characters treat Adrian like an incompetent dummy instead of a human being with a medical issue) and in the common/slang use of the term “OCD” (meaning “I like to alphabetize my bookshelf” or “I like to eat all the green Skittles first”). If you felt that you had to order your books in ascending order by height, otherwise your mother would die in a car crash, then you might have OCD (and should ask a counselor to lend you a hand, because you should not have to deal with those feelings alone). People have very little real concept of the term.

But why is this a big deal? Well, self-blame is already one of the issues that can plague an individual with OCD. There are plenty of mental disorders that can have self-harming side-effects, and that definitely goes for anxiety disorders. If a person with OCD thought that their intrusive thoughts were their own fault--not the fault of a chemical imbalance that can often be treated with counseling and/or medication--there would be high risk for self-harm, not to mention a deepening of depression (often comorbid with anxiety disorders). If family members or friends were under the impression that it was just a matter of self-control, they would not be able to provide the kind of support (emotional or medical) needed to actually deal with the issue.

But, back to the work itself. There is a lot of perceived violence in this book. That’s an important factor, a good and necessary factor. Dillon allows readers a glimpse of what it’s like to live with intrusive thoughts and the coping behaviors used to counter them.

If it weren’t for that one sentence, that one completely counter-productive realization of Nao’s at the end, it would be an invaluable tool for understanding OCD, akin to Ellen Forney’s exceptional graphic memoir, Marbles, and manic depression. As it is, The Nao of Brown is a beautifully illustrated work that is an interesting read up until around page 191/the questionable resolution.

It’s difficult to assign a book like this a rating, since 95% of it is lovely. I can’t help but wonder what kind of reaction it would have received if it had said that depression--or, hell, cancer--was the fault of the person who had it. OCD is a medical issue. That one writing mistake renders the whole book glib, and makes for a crude understanding of what was otherwise so deliberately well-depicted.

Instead of a star-based or grade rating, I’ll suggest you read it, but that you ignore page 199.

Suggested reading:

Alison Bechdel’s Are You My Mother

Monday, August 5, 2013

Professional

Thinking about ethics, thinking about my personal beliefs, thinking about how much I hate anything phony. Thinking about applying for an office job again, thinking about how I might be judged for this (from both sides), thinking about my "image." Thinking about personal brands, thinking about the hard-won pride I have in my personal identity, thinking about how these things could be perceived as counter in a more conservative workplace. Thinking about how I am still out of touch with the culture of this place, thinking about how I want to be involved in the writing/publishing community but have had no luck thus far, thinking about how I wish I could open a comics shop here. Thinking about money, thinking about the tens of thousands of dollars of debt I am accumulating in pursuit of my graduate degree, thinking about priorities. Thinking about how much I love my Masters program, thinking about the love I get from that community, thinking about how much I want to move to Michigan. Thinking about how much writing I have done in the last few days, thinking about how good that has made me feel, thinking about the fear of never being good enough. Thinking about success, thinking about personal measurement of success, thinking about the Goodness of Art. Thinking about comics, thinking about drawing, thinking about drowning in work I love that I never get paid to do. Thinking about the concept of "work," thinking about how lucky I am to make these choices, thinking about the partner who supports me while I think about these things. Thinking about privilege, thinking about guilt, thinking about Saint Francis of Assisi.

Thinking, thinking, thinking.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)